People have depicted monsters as long as they have had fears – that is, since the beginning of time. By giving them shape, they can face up to them and fight them. Human imagination has been inhabited for millennia by wolfmen, dog-headed gods, aliens, trolls, giants, devils, demons and vampires. From the outset, their forms have been a mix of the imagined and the experienced: they are hybrid beings constructed from known forms (animals, plants). They have journeyed from the stories of archaic myths, through fairy tales, and from examples of fine art to the illustrations of children’s books.

The illustrations of contemporary Hungarian graphic artists are at the centre of our exhibition. The first group focuses on those mythical beings that are the best known characters of tales: dragons. In the children’s literature of today, it is difficult to find a destructive, wicked dragon. The insecure, harmless dragons derived from István Csukás’s Süsü, such as Tihamér and Kajtikó in the tales of Gyula Sipos or Olga Zágoni are the norm. The friendly, helpful dragon of Far Eastern culture appears in the tale of Petra Finy, in which the Golden Dragon is the companion of the White Princess.

The traditions of depicting monsters and imaginary creatures, spanning millennia, live on in the illustrations of children’s books. Such are the mythical heroes’ fights against the monsters (e.g. Hercules defeating the Hydra) or the long list of dragon-slaying heroes. These appear in classical form in some places, such as the drawings of Krisztina Rényi or Ildikó Horváth, and are adorned with humor elsewhere, as in the drawings of Norbert Nagy.

Besides dragons, devils and witches are well known characters in the ranks of monsters in tales. Their forms are made less threatening through abstraction and the tools of stylized drawing by children’s books illustrators, as demonstrated well by the compositions of László Herbszt.

Hybrid beings present, without doubt, the most liberated sphere of artistic fantasy. Imaginary creatures created from a cross of man and animal or animal and animal have long been figures in ancient pagan religions. They are the creations of playful fantasy and share a deep tie to the imaginative creativity of children. These beings of various shapes and colors are brought to life by creative artistic liberty in the drawings of Jacqueline Molnár.

The appearance of monsters in children’s literature often serves the purpose of giving shape to children’s fears. Réka Hanga gives friendly form to Zsolt Adamik’s monsters of Bibe Hill, while the charmingly extravagant drawings of Annabella Orosz recall the lurking monsters of children’s bedrooms. András Dániel’s drawings, on the other hand, neutralize the meeting with the imaginary monsters under the bed with playful humor.

The monsters of children’s literature are doing well, thank you, flourishing and multiplying in tales and their accompanying illustrations. And these are certainly useful monsters, not only because they give shape to children’s fears, but because they embody the boundless fantasy world of the fine arts.

Exhibiting artists: Baranyai (b) András, Bölecz Lilla, Cselőtei Zsófia, Dániel András, Felvidéki Miklós, Ferth Tímea, Grela Alexandra, Hanga Réka, Herbszt László, Horváth Ildikó, Kállai Nagy Krisztina, Kecskés Judit, Kun Fruzsina, Kürti Andrea, M. Nagy Szilvia, Makhult Gabriella, Maros Krisztina, Metzing Eszter, Molnár Jacqueline, Nagy Norbert, Nagy Zoltán, Orosz Annabella, Remsey Dávid, Rényi Krisztina, Rofusz Kinga, Szegedi Kata, Szimonidész Hajnalka, Takács Mari, Vihart Anna

Curator: Emese RÉVÉSZ art historian

The exhibition is in the offical program of Budapest Art Week. The exhibition is sponsored by Pagony Publising.

Due to the public health emergency the opening ceremony of ‘My Little Beast’ exhibition will be postponed. Pieces from the exhibition will be presented on this page.

The online exhibition is available to visit on this page. Please click on the picture galleries at the bottom of the page ( CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS V | CHILDREN’S WORKS V ).

Opening: 2020. 04. 15. 17:00 – cancelled!

Opening speech by: Emese RÉVÉSZ curator

Music: Musica Moralia

On view: 2020. 04. 15 – 07. 08.

Contemporary Artists

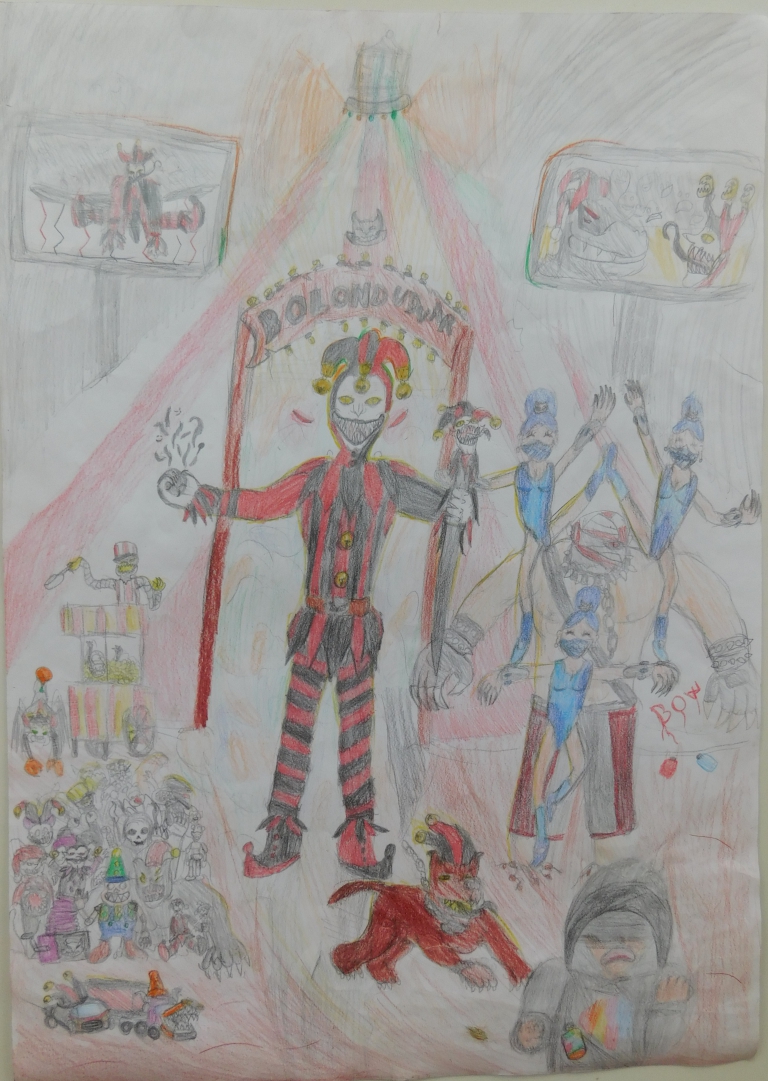

Ever since independent children’s culture even became a matter of discussion, figments of monsters have had a place therein. We speak of such figures that have resided in legends, tales and the fringes of the world recognized by the natural sciences. A host of paintings of and drawings of them has long been evidence of their existence, bringing their forms into tangible, physical proximity from here and there through the objective description of observation. However, since the scientific objectivity of the Enlightenment swept out the last little basilisk from the strictly maintained order of creatures whose existence can be physically proven, imaginary beings have been placed in the quarantine of myths and tales, finally finding a home in the Garden of Paradise of art. From here, they have ventured into children’s culture, where they do certainly feel at home, as they themselves are born of two worlds, just as the children’s universe draws no sharp dividing line between reality and the imagined. The tamed forms of the imaginary beings of monsters have become common denizens of children’s bedrooms, as redolent, colorful stuffed animals present at the child’s birth, appearing on keychains attached to book bags, chortling on the pages of children’s books and in the frames of films, causing fright on the screens of computer games, gradually laying the groundwork for the consumption of the even more chilling creatures of mass adult culture. The monster boom of the present day shows that we have never more loved to be afraid, or we have never been more afraid.

Wolfmen, dog-headed gods, aliens, trolls, giants, devils, demons and vampires have inhabited the history of art for millennia. From the beginning, their forms have been a blend of the experienced and the imagined: they take the shape of hybrid beings constructed from known forms (animals, plants). They have journeyed from the stories of archaic myths into tales, and from specimens of fine art into the illustrations of children’s books. Practically all iconic forms of artistic depictions of monsters can be found in the illustrations of children’s books, although adjusted in content and appearance to the particular needs of the age group reading or looking at the book. At the focus of our exhibition are the illustrations of contemporary Hungarian graphic artists. We hope our selection represents the rich diversity of style and depictive quality of today’s Hungarian illustration.

From Seven Heads to One – Dragons

In European culture, the form of the dragon is traditionally a hybrid, reptile-like being with the characteristics of a snake and a lizard that may have fangs, claws, wings or fins, depending on whether it is a creature of the air, the water or the land. In Kinga Rofusz’s illustrations for Magic Flute, the drawing of the little princess locked in the tower catalogs the characteristics of the dragon as such: “large head, membranous wings, sharp teeth and claws, a crest and long spiny tail, fire, steam, stink and soot…”. In contemporary illustrations, the traditional artistic appearance of these beings is sometimes well represented, such as in the beings of Krisztina Rényi which recall Renaissance dragons, or the fine, scally art nouveau snakes of Zsófia Cselőtei. In the children’s literature of today we find wicked, destructive dragons only occasionally. The insecure, benevolent dragons familiar from István Csukás’s Süsü are far more typical. So it is in the fine pencil drawings of Anna Vihart, in which dragons are not frightening beasts, but sophisticated and sensitive beings with noble bearing. Alexandra Grela on the other hand exploits the ambiguity of interpreting images when it comes to light in the course of the story that the dragon’s heads, flashing their sharp teeth, do not pose a threat, rather they sing with abandon. An effective tool for “taming” dragons is humor, which we see in the drawings of Krisztina Kállai Nagy, bursting with color, where the seven-headed dragon visits the dentist or pretties up.

The Dragon-Slaying Hero

The dragon-slaying hero (or the hero who triumphs over the beast) is a recurring element in both the traditions of myth and magical tales. In the visual arts, it is a universal visual topos, an archetype or, in the words of Aby Warburg, a “pathos formula”. In classical Hungarian book illustration, illustrators such as Ádám Würtz, János Kass or Károly Reich have created the emblematically concise pictorial precursors of the scene for the tales of John the Valiant and Elek Benedek. In the blue-toned images of Lilla Bölecz, the Hydra-slaying hero appears based on traditional examples. András Baranyai, on the other hand, resolves the myth of the meeting between Theseus and the Minotaur with humor. The drawings of Ildikó Horváth, in which the visually threatening features of the monster are its form towering over the boy, its heads slithering like snakes and its red color, are anchored in the tradition of classical Hungarian illustration. In the tale of Petra Finy, the White Princess’s companion is the benevolent dragon of the East, which is given a soft and protective form in the paintings of Mari Takács. Norbert Nagy relieves the tension of the story with the tools of humor when, instead of physical harm, he depicts the knight triumphantly treading on the dragon groggy from wine.

Devils, witches, ghosts

It is difficult to find any frightening beings in the children’s books of today. The illustrators deploy the numerous tools of graphic art endeavoring to alleviate or remove the threatening features of monsters. Their process can be best described with the concepts of aestheticization – abstraction – stylization. Aestheticization presents fantasy beings with an expressly artistic, sophisticated set of illustrative tools. Krisztina Maros’s creatures included in Dániel Varró’s collection of viking legends in verse free the monsters of all traditionally frightening features with their rounded forms and serene colors. In László Herbszt’s two-dimensional, decorative forms, devils and vampires are abstracted with notional, stylized pictorial signs. Jacqueline Molnár mitigates the horrific phenomenon of a skeleton woman returned from the dead with abstract, neon colors.

Hybrids and Other Fantasy Beings

Hybrid beings present unequivocally the most unconstrained area of artistic fantasy. Imaginary beings created from a cross of human and animal or animal and animal have long been actors in ancient pagan religions. In the drawings Szilvia M. Nagy made for the volume of verse by Viktor Szigeti Kovács, the bird-like hybrid beings are depicted in scientific detail. In the illustrations of children’s books, hybrids lose their monster-like features and can be seen rather as playful, fairytale fantasy creatures. This game of forms shares deep roots with the imaginative creativity of children. In the drawings of Jacqueline Molnár, the freedom of artistic creativity brings to life these beings of various colors and forms, providing the background for the mythological Greek heroes of both Lightning-throwing Diabáz and Transformation Tales. Gábor Schein’s tale in verse, Irijám and Jonibe, which tells the origin story of a new creature born of the love between the fish queen and the bird king, also has roots in mythology. Kinga Rofusz’s lyrical, symbolist-surrealist world of imagery gives human faces to the animal forms. In the monochrome, frottage-like images of Dávid Remsey for the stories of Sündör and Niru, extraordinary material effects are evoked, with the crumbly, stone-line skin of Bocskoján and Tivonul Buffogó’s tightly woven mask of vegetation. In the drawings of András Dániel the hybrid fantasy beings are everyday normal, full-fledged residents, who indirectly lead readers to accept differences. “All are travelers alike, but how varied are their kinds!” – the little boy who stands in as an elevator operator in the empire of the fantasy beings exclaims with surprise.

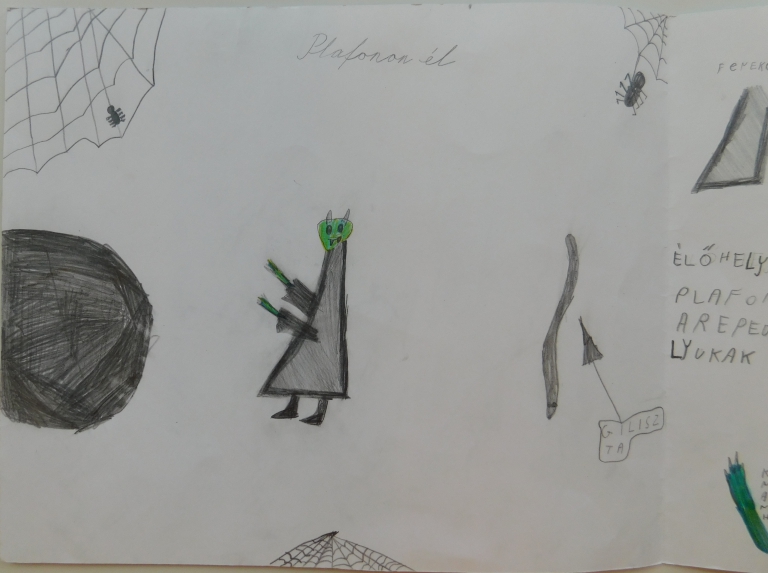

Scary Monsters

The presence of monsters in children’s literature often serves the goal of giving shape to one’s fears and anxieties, resolving them with the power of evocation. Annabella Orosz’s sweetly extravagant drawings summon the lurking monsters of children’s bedrooms; her kind-faced creatures, dissolving in pastel colors, can effectively help “talking out” anxieties. In András Dániel’s volume entitled What was Jacob Looking For Under the Bed?, his main protagonist is introduced in the murky danger zone under the bed. In his drawings, he gives form to Hómama, who eats little boys for supper, to the sad Lepénylény, and to the frightening Szőrzike. In the meantime, Dániel successfully incapacitates the monsters’ power to scare with his grotesque, humorous drawings. A pseudo-scientific taxonomy of monsters is established following the traditional forms of the creatures in Zsolt Adamik and Réka Hanga’s Bibe Hill Monster Guide. To this end, the artist mobilizes the traditional types of images used for visual communication in the natural sciences, imitating antique crests, codex illustrations, botanical drawings, daguerreotypes created with fiber optics, photographs from family albums or old newspaper photos. The rounded forms of the drawings, their serene colors mitigate the entire verisimilitude of the world of monsters in a refreshing manner, which serves well the real purpose of this author of the imaginary world: to alleviate children’s fears. As the author puts it in his introduction: “If you know the monster, you will no longer have to fear anything else” – adding: “Monsters exist so that we may see what we fear.”